Performing Global Model Analysis with TCAV

LIT contains many techniques to analyze individual predictions, such as salience maps and counterfactual analysis. But, what if you want to understand more global characteristics about a model, and not just its behavior on a single example/prediction? Or what if you have too many input features or your input features are too complicated that saliency maps aren’t as insightful? One technique that can help here is called Testing with Concept Activation Vectors, or TCAV. For more technical details on how TCAV works, see our LIT documentation on the feature. This tutorial provides a walkthrough of using TCAV inside of LIT.

TCAV shows the importance of high-level concepts on a model’s prediction, as opposed to showing the importance of individual feature values (such as tokens for a language model). Another difference is that TCAV gives aggregated explanations for many data points (a global explanation) instead of one data point at a time, like saliency maps (a local explanation).The concepts are defined by the user creating a subset of datapoints (a “slice” in the LIT tool) containing the concept they wish to test. LIT runs TCAV over the slice to determine if that concept has a positive or negative effect on the prediction of a given class by a classification model, or if that concept has no statistically significant effect on the prediction of that class.

Running TCAV in LIT

Use Case

One of our LIT demos is a BERT-based binary classifier of movie review sentences (from the Stanford Sentiment Treebank dataset). It classifies the sentiment of sentences as positive (class 1) or negative (class 0).

Let's try to determine if there is any correlation between other language features, such as the use of the terms “acting”, “actor”, and “actress”, or mentions of music, with the classification of sentiment. This can help us understand what concepts a model is sensitive to, and when and how errors may occur.

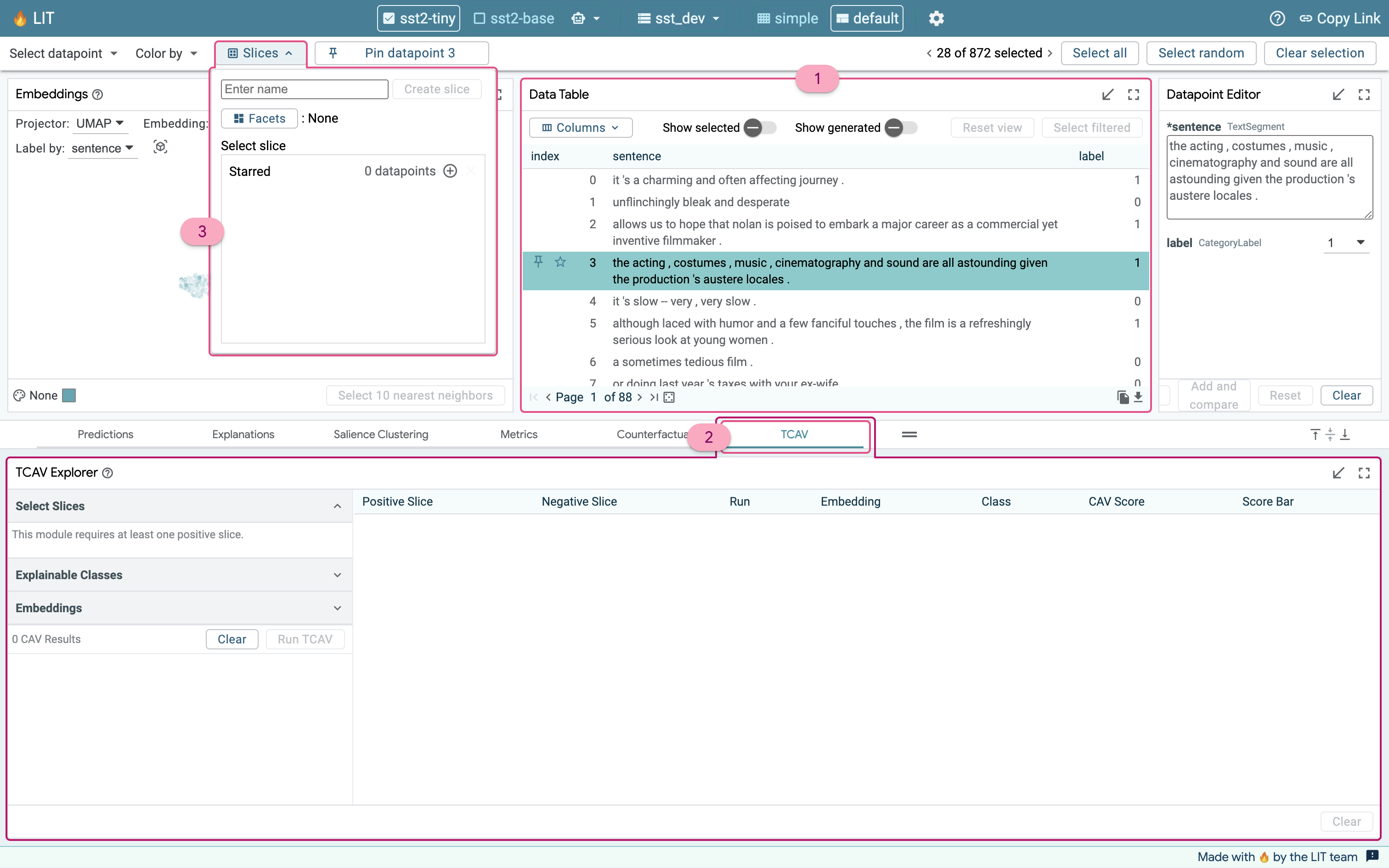

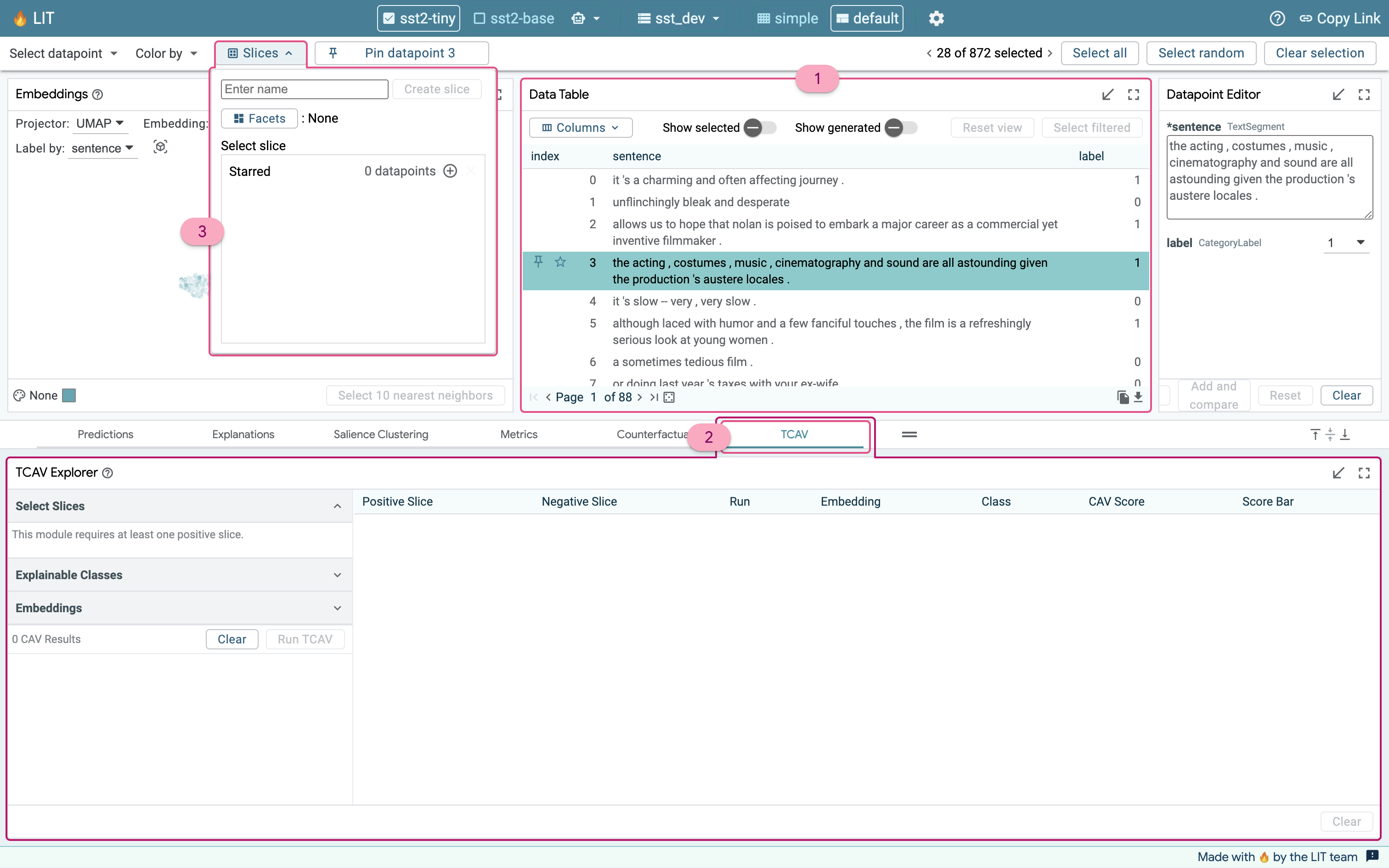

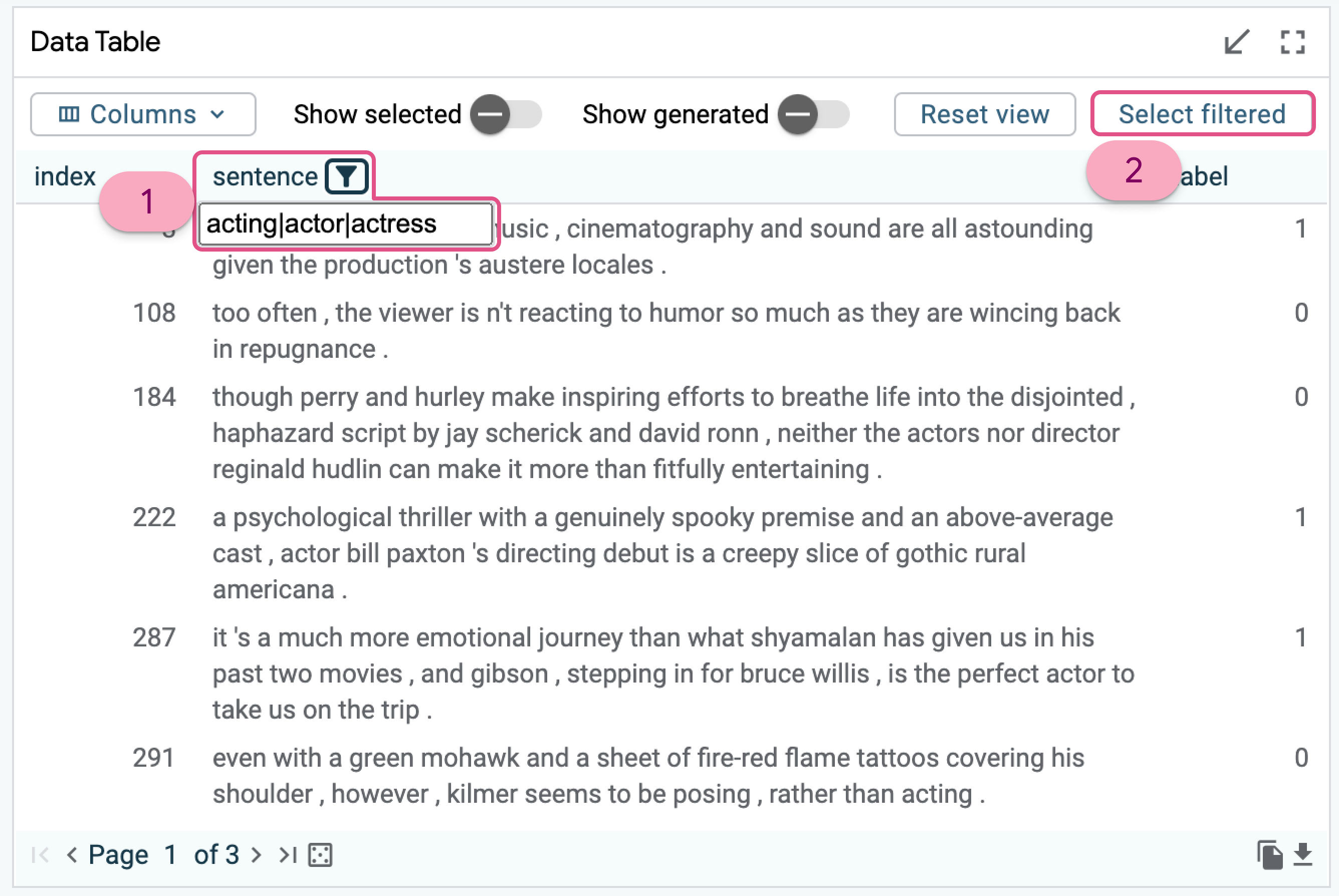

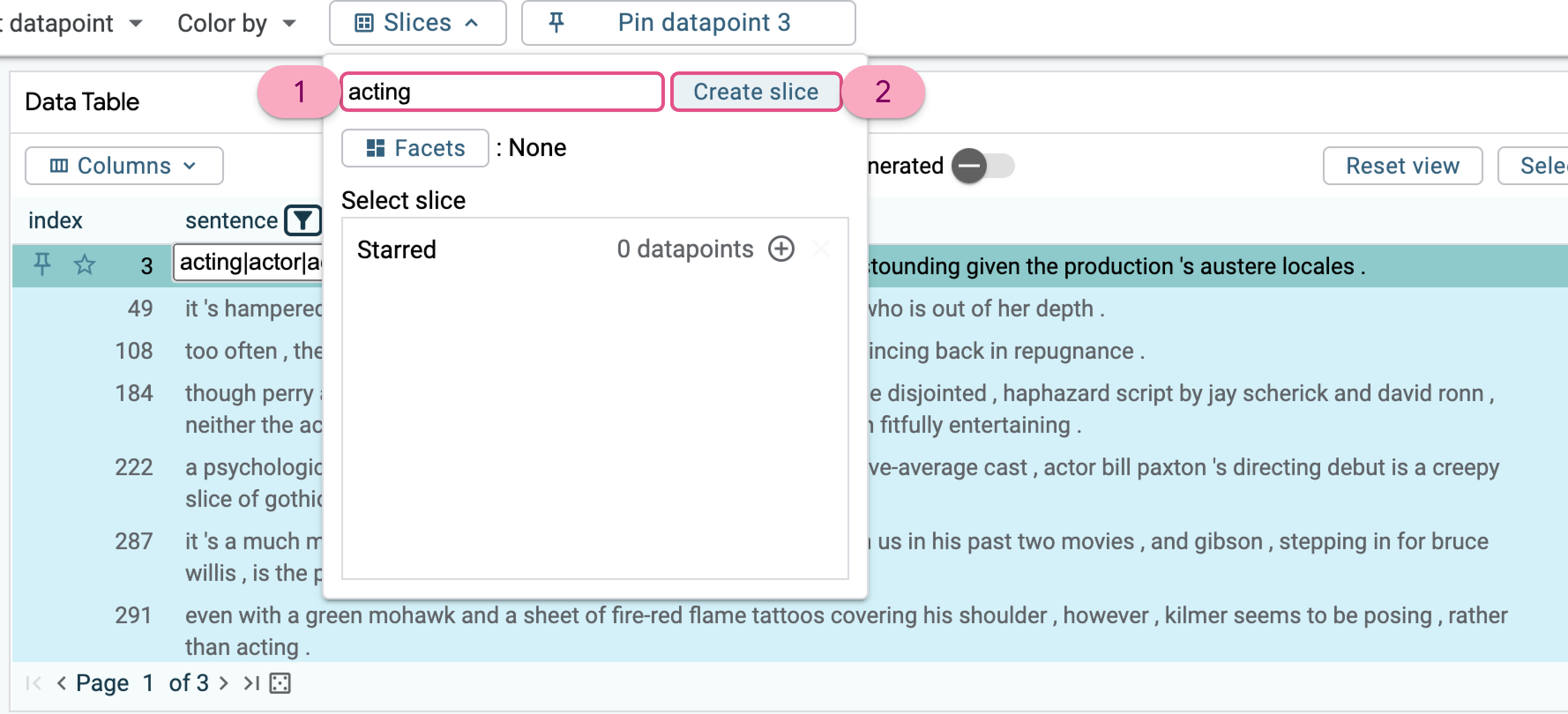

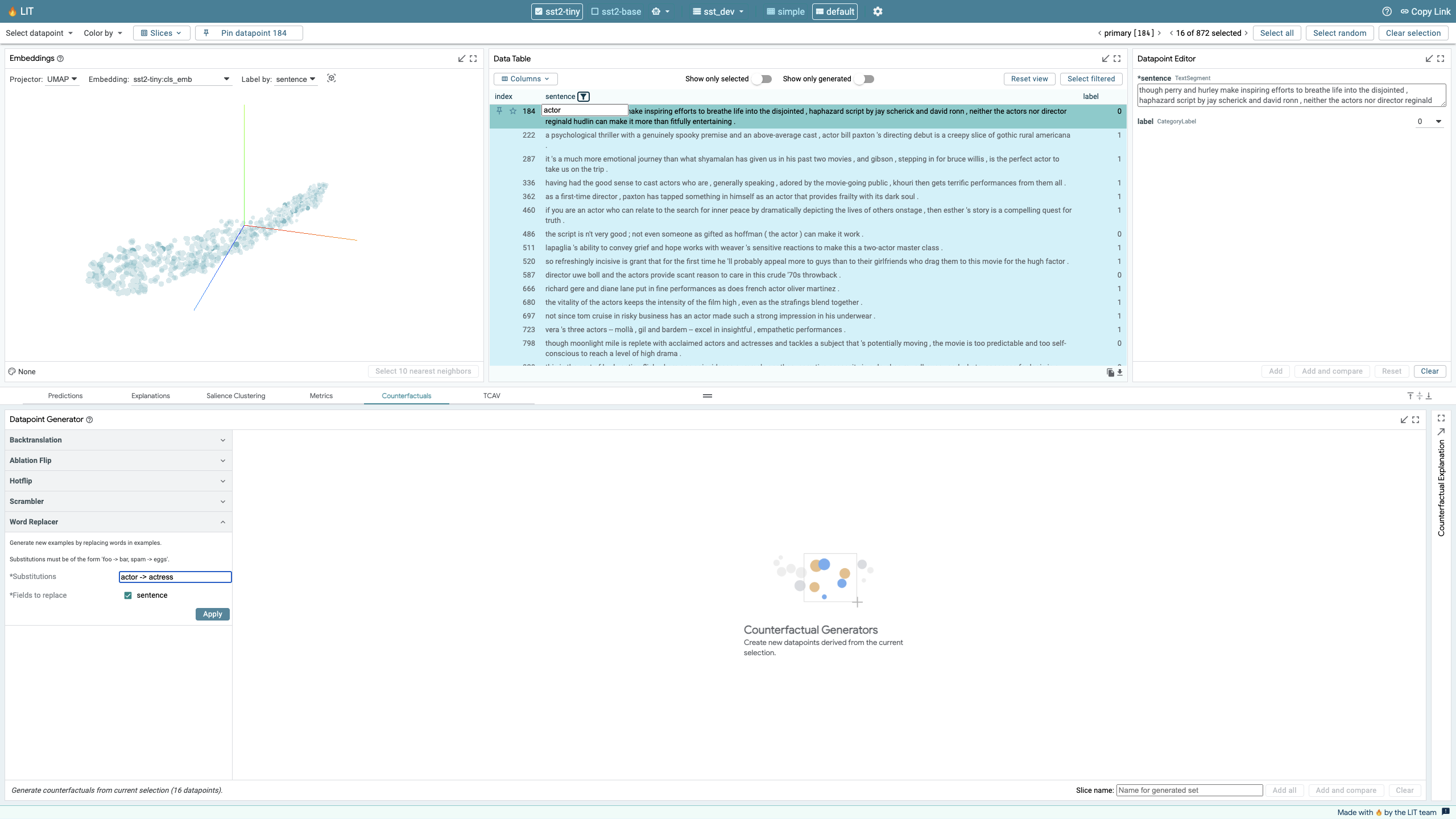

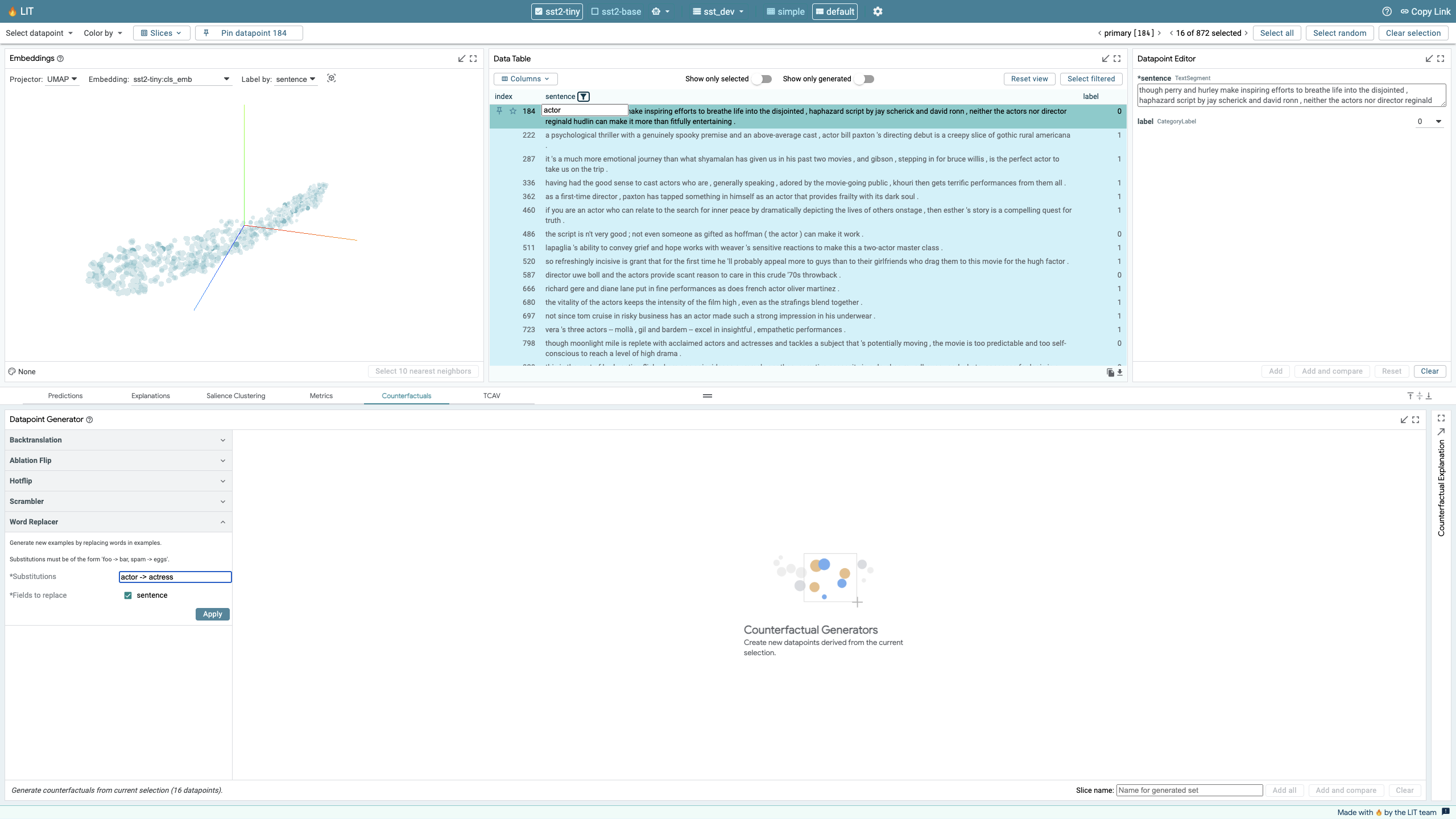

Create a Concept

First, let’s test if the mention of the phrases “acting”, “actor”, or “actress” has any influence on the model’s predictions. To test a concept in LIT, we need to create a slice containing exemplary datapoints of the concept we are curious about. We can go to the data table, and use the search feature of the “sentence” field and search for “acting|actor|actress” to search for all mentions of those three terms. We then select all those examples using the “select all” button in the Data Table, expand the minimized Slice Editor, and use it to create a new slice named “acting”, containing those 28 datapoints matching our query.

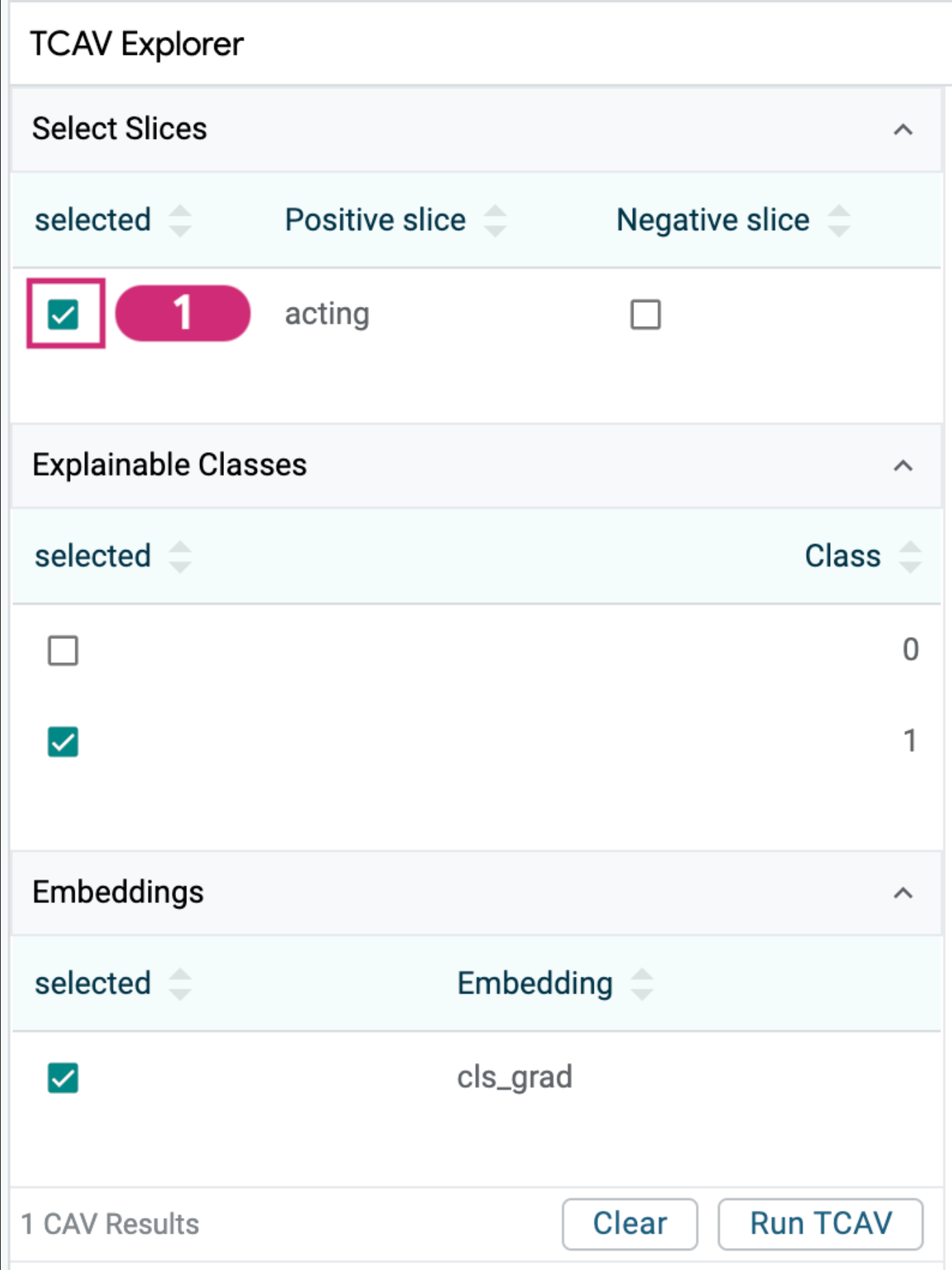

Now we can go to the TCAV module and select our options to run the method. There are three sets of options to select.

-

Slice selection: You’ll notice that each slice can be selected through a left-side checkbox. You can test multiple concepts at a time by selecting more than one slice, if desired. Slices can also be selected as a “negative slice” through a right-side checkbox. For basic TCAV use, we don’t select any negative slice. See the below section on “Relative TCAV” for use of that option.

-

Model class selection: The default selection of class 1 means that TCAV will test to see if the concept selected has influence over the model predicting that class (which in this case means positive sentiment). If we were to change this to class 0, we would be testing to see if a concept has influence of the model predicting negative sentiment. For a binary classifier, you would only need to test one of the two classes because if a concept has a positive influence on class 1, then it would automatically have a negative influence on class 0. For multi-class classification with many possible classes, changing the explainable class is more important, in order to test out the concepts’ influence across any specific class.

-

Embedding layer selection: TCAV requires that a model be able to return a per-datapoint embedding during prediction for use in its calculations. For models that return multiple per-datapoint embeddings at different layers of the model, you may find that certain concepts have influence at different layers. For example, TCAV research on image models found that embeddings early in a model’s architecture had significant concepts around color and basic patterns and embeddings later in the architecture had significant concepts based around more complex patterns. Typically, we recommend choosing the layer closest to the prediction layer.

For our use-case, we click on our “acting” slice as the concept to test, and can use the default selections of explaining class 1 and using the “cls_grad” embedding, which is the only per-datapoint embedding returned by this model. In our BERT-based model, the “cls_grad” embedding is the activation of the “[CLS]” token, which captures information about the entire sentence to be used for the final classification layer of the model.

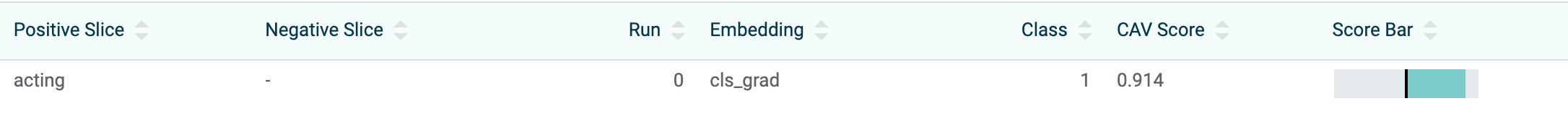

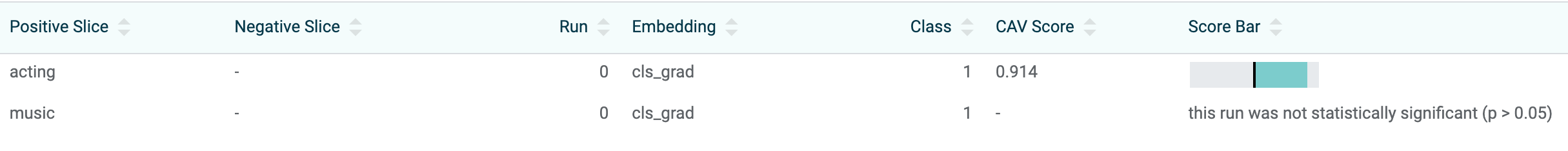

Interpreting TCAV scores

Once we run TCAV, we see an entry in the table in the TCAV module for each concept tested. Each concept gets a CAV (“Concept Activation Vector”) score between 0 and 1 describing the concept’s effect on the prediction of the class in question. What matters is where the blue bar (CAV score) is relative to the black line (reference point). The reference point indicates the effect that slices made of randomly-chosen datapoints outside of the concept being tested has on prediction of the class. For a well-calibrated classifier, the reference point will usually be near 0.5 (i.e. no effect).

A blue bar extending right or left of the black line means the concept is influencing the prediction. If the blue bar extends to the right of the black line, the concept is positively influencing the prediction. Conversely, if the bar extended to the left, it is negatively influencing. In either case, the larger the bar, the greater the influence.

In our example, the CAV score of ~0.91 indicates that our “acting” concept has a strong positive effect on the prediction of this class. So we have found that this concept has a positive effect on predicting positive sentiment for our classifier.

Now, let’s try a different concept. We’ll go through the same process, except with datapoints containing the word “music”, so we can see if mentions of music in a review have a significant effect on prediction. We can repeat the steps above to select matching datapoints, create a slice of these datapoints, and run TCAV on that slice. After doing so, we get a new line in the TCAV table, but it indicates “this run was not statistically significant”. That means that TCAV did not find a statistically significant difference between the effect of this concept versus concepts made of randomly sampled datapoints. So, we have found that mentions of music don’t seem to have any specific effect on predicting positive sentiment in this classifier. For details on this check, read the LIT TCAV documentation.

Creating Useful Concepts

As you can imagine, it is important to select a set of datapoints that capture the concept you wish to test. If your datapoints capture more concepts than what you wish to test then the results won’t be what you expect. In practice, this can be difficult to do with precision as different language features overlap in ways we don't always intuit.

One way to overcome this challenge is providing more data for TCAV to analyze. If you do not select enough datapoints, your set of examples might capture more, different, and/or overlapping concepts than you intend. A good rule of thumb, as seen in ML interpretability research, is to use at least 15 examples for a concept, but it can differ based on model type, data format, and the number of total examples in your dataset in LIT.

Imagine if, when we created a concept by searching for the word “music”, that every time “music” is used in a review, that review happens to be glowingly-positive. Then our concept doesn’t only capture the concept of music-related reviews, it also captures a set of very positive reviews. This introduces a bias into our analysis process. The music concept we created would obviously be shown to have a positive influence on prediction, but it might not be due to the music itself. So, take care in defining concept slices, and look at the datapoints you have chosen to ensure they represent the independent concept you wish to test.

Concretely you can sort your dataset with respect to concepts created through TCAV (e.g., using cosine similarity) to do a qualitative check: does the sorting make sense to you? Does it reveal something that CAV learned that you didn’t know about? Sorting datapoints with respect to concepts in a feature that will be added to LIT in the future.

If the sorting reveals unwanted correlated concepts, you can help the CAV to “forget” this concept by collecting negative examples with only the correlated concepts. For example, if your “stripes” images all happen to be t-shirts, use non-striped t-shirts images as negative examples and create a relative concept as described below. This will help the concept to not contain information about t-shirts. In some cases, you can debias accidentally added concepts using causal analysis.

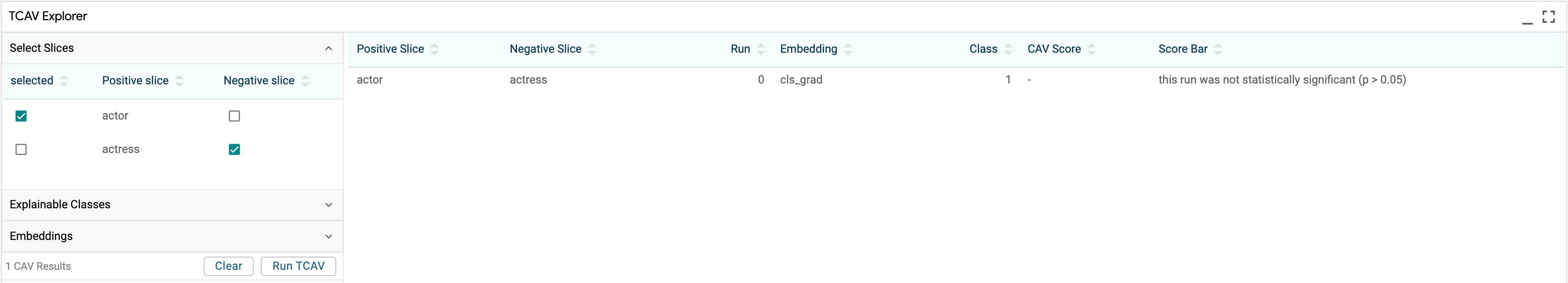

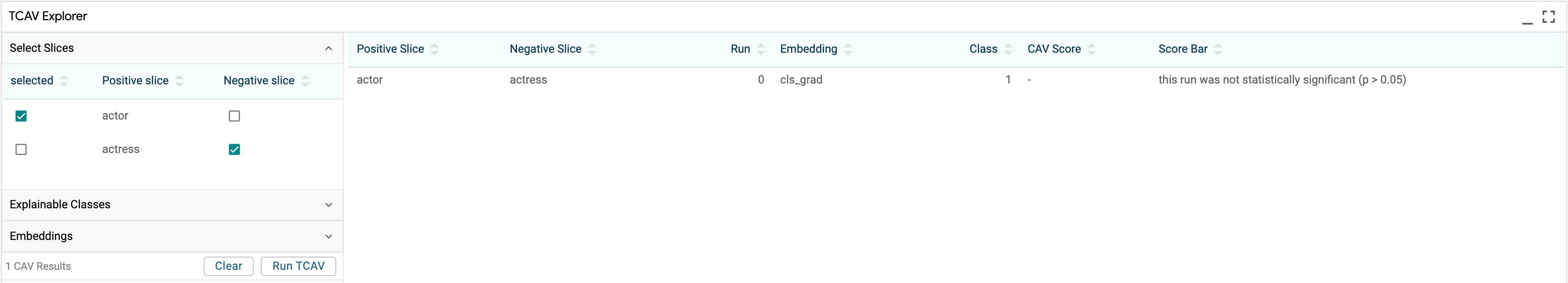

Relative TCAV

In the “Select Slices” menu, you’ll notice that there are checkboxes to select a slice as a “Negative slice” in addition to the checkboxes to select the concepts to test. You can test a “relative concept” by selecting one slice as the positive slice and another slice as the “negative slice” and running TCAV that way. Testing a relative concept allows you to see if adjusting datapoints from containing one concept to containing another will generally have an impact on classification.

For example, what if we wanted to test if the use of the gendered terms for acting professionals – “actor” for males and “actress” for females – has an impact on sentiment prediction? Instead of testing concepts of “actor” and “actress” separately for significance, you could generate a set of gender-flipped examples and use Relative TCAV to explore the differences. To start, create an “actor” slice with all datapoints containing the word “actor”. Then use the Word Replacer counterfactual generator to change all instances of “actor” to “actress” in those datapoints, add those newly generated datapoints to the dataset, and save them as a slice named “actress”. Next, in the TCAV module, set the positive slice to “actor” and the negative slice to “actress” and run TCAV. The resulting concept is shown to be not-significant. This means that our classifier doesn’t seem to be sensitive to using the gendered terms actor over actress in the predictions of review sentiment.

Conclusion

TCAV offers a way to look for global characteristics about classification models by analyzing the influence of concepts, represented as user-curated slices of exemplary datapoints, on class predictions. It can be very useful for hypothesis generation and for testing theories generated by other techniques. As with any interpretability technique, it is only one piece of a larger puzzle.

Care must be taken in defining concepts to ensure that they represent what you expect them to and do not contain surprising or spurious concepts (such as defining a concept based around inclusion of the word “music” in sentences where all those sentences also happen to contain glowing, positive reviews, whereas the wider dataset contains both positive and negative reviews). We provide some ways to do this above.

By including TCAV in the LIT tool, we encourage people analyzing ML models to investigate global model behavior through concepts. No single interpretability technique can fully answer the questions we have about model behavior, but the more techniques that are accessible, the more power we have to improve model transparency and interpretability.